The novel, The Grapes of Wrath, you’ve probably heard of. The biography, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, and the poem, Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, maybe not. All three are powerful, compelling and enduring explorations of the human condition, the one criterion all classics must meet. All three touched me to my core.

Because I want you to read all three I won’t spoil them by going into detail on the stories. Instead, I’ll explore my favorite scene/story/stanza to give you a flavor for what lies within.

Without further adieu…

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

My connection to it: I didn’t read The Grapes of Wrath until I was in my 40’s. Why? Maybe for the same reason most of you haven’t: Because I heard it was boring. Wow, was I ever wrong.

Short description: The novel chronicles the experiences of the Joads as they travel from Oklahoma to California, in search of a new life after the Dust Bowl droughts of the 1930s lay waste to their farm and threw the entire family into abject poverty. Steinbeck alternates back and forth between chapters devoted to the Joad’s story and descriptions of various conditions extant during this period.

The scene that captures the heart of the novel: The Grapes of Wrath is a story about the profound beauty that can arise out of oppression and suffering. In fact, if I had to choose one word to describe this novel it would be pathos, defined in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as, “an element in experience or in artistic representation evoking pity or compassion.”

I might have picked the controversial ending scene of the book but didn’t want to spoil it. The following scene in the novel captures this pathos just as beautifully as the ending.

Two Okie boys traveling with their families along Route 66 from Oklahoma toward California walk into a roadside café, barefoot and hungry. They stare through a display case at some candy and look like they’ve seen manna from heaven. They ask the waitress how much the candy costs.

She says, “How much have you got?” The boys say they have one penny. She says, “Them’s two for a penny.” They give her the penny, take the candy and rush out, smiling ear to ear.

A trucker drinking coffee at a table with his colleague says to the waitress, “Hey, them wasn’t two-for-a-cent candy. Them was nickel apiece candy.” To which she responds, “What’s it to you?”

The truckers get up, put some money on the table and walk out. The waitress takes the money then rushes to the door. “Hey! Wait a minute. You got change.” The trucker replies, “You go to hell.”

Just a simple scene about generosity and compassion in tough times. When the great singer-songwriter Kris Kristofferson saw this scene play out in the 1940 film version of Grapes of Wrath starring Henry Fonda, he was so moved that he wrote a song about it called Here Comes That Rainbow Again. Johnny Cash said it was his favorite song of all time. Check out the video HERE. Brings tears to my eyes every time I watch this clip.

The hard times our world has experienced this past year due to COVID-19 make the themes of Steinbeck’s masterpiece all the more resonant today. It’s heartening to know that the pain and suffering on the scale of the Dust Bowl-Great Depression and COVID-19 often awakens the best in humanity from the slumber of complacency that often reigns during good times. Give The Grapes of Wrath a read. You, and your heart, will be the better for it. Here’s the Amazon LINK.

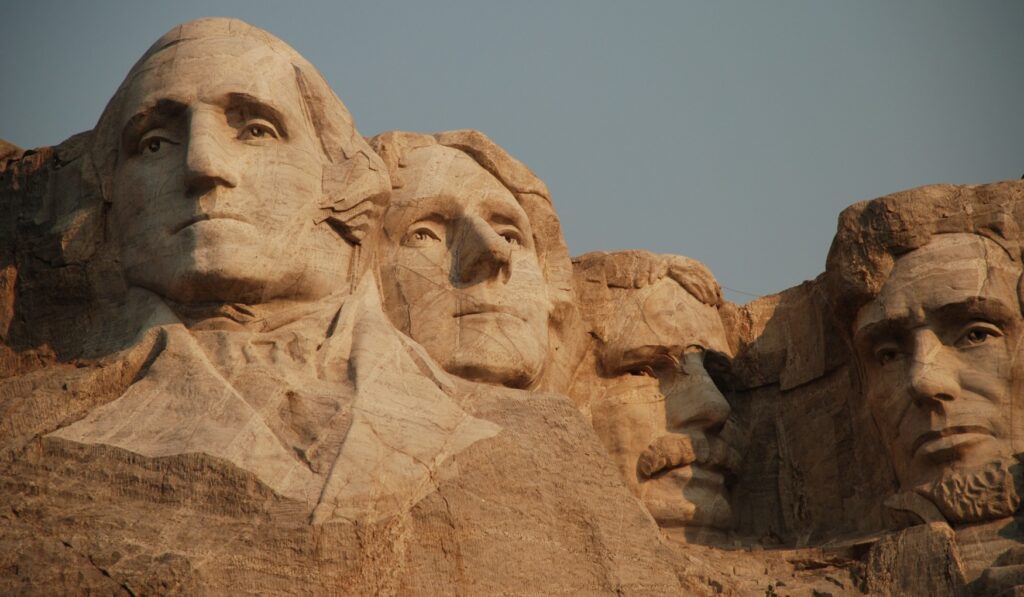

The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt by Edmund Morris

My connection to it: Known as one of the best biographies ever written, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt chronicles TR’s life from birth until the day in September, 1901, that he became president upon the assassination of William McKinley. I first read it in 1991 after finding it in my roommate’s bookcase. TR quickly became, and has remained, my favorite president because of this Pulitzer Prize winning masterpiece.

As a Hollywood screenwriter I wrote a movie in 2006 about TR based on the book. Nerding out even further, I named our Labrador retriever Teddy and joined the Theodore Roosevelt Association.

Short description: Born into an aristocratic family (his father was a founding board member of both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History), TR was an asthmatic, sickly child. To fight this condition, his father urged a strenuous physical life for TR. This resulted in a childhood and early adulthood dominated by outdoor activity, leading to TR’s lifelong love of animals, hunting, ranching and horseback riding. This love of nature eventually led President Roosevelt to conserve 230 million acres of U.S. land, making him, arguably, the most consequential environmentalist of all time.

At 25 TR became the Republican Leader in the New York State Assembly, then a U.S. Civil Service Commissioner, New York Police Commissioner, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Governor of New York, Vice President, and finally President of the United States.

The story that captures the heart of the book: The adventure that defined TR’s life from age 25 until his death in 1919, and the period my screenplay covered, was the two years he spent as a cowboy rancher in the Badlands of Dakota Territory. It defined his life because of the reason he went there in the first place.

In early 1884, TR was a wildly successful 25 year old New York Assemblyman with a future as bright as the sun. Madly in love with his young wife, Alice, the couple was expecting their first child in mid-February. But tragedy struck on Valentine’s Day, 1884, when Alice died two days after giving birth.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t all. On the same night, and in the same house, TR’s beloved mother, Mittie, also died, of Typhoid Fever, something they all thought was just a bad cold only days before.

Two unexpected deaths, on the same night, in the same house, of the two people he loved most. And on Valentine’s Day of all days. Writing in his journal that night TR wrote an ‘X’ across the page and one sentence below it:

“The light has gone out of my life.”

His soul shattered, TR quit politics and move to the Badlands where he owned two ranches. He spent his days riding alone in the Badlands, doing arduous cowboy work like rounding up and branding cattle and reading and writing at his Elkhorn Ranch which was 26 miles from the nearest town of Medora.

This life of peaceful tranquility, hard physical exertion and immersion in nature produced two developments that allowed TR to move forward and achieve the greatness he did. First, it healed his broken heart.

Second, by working and living among cowboys and “coarser folk,” TR came to know the people he subsequently viewed as the bedrock of America. Before his adventures in the Badlands TR was, frankly, an aristocratic snob. He often said that were it not for these years out West he never would have become president of the United States.

The adversity TR overcame is an inspiration for all of us no matter the state of affairs in our world, but especially now with our entire planet battling the scourge of COVID-19.

The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt is by far the best biography I’ve ever read, and I’ve read a ton of them. Read it and you will understand why Theodore Roosevelt is chiseled into Mount Rushmore. Here’s the Amazon link.

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard by Thomas Gray

My connection to it: Written in 1751 by Thomas Gray, Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard is known as one of the greatest poems of the English language. I was introduced to it in my 20’s by my godfather Tom Tuttle, a brilliant English major at Yale. I’ll never forget the summer night on the porch of his lake house in Crab Lake, Wisconsin, when he recited several of the 32 stanzas of Elegy. After reciting this particular stanza…

“Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds.”

…He looked at me and said, “Wow! How great is that?!” His passion piqued my interest and led to me exploring this and other classic poems.

Short description: Gray wrote the poem after seeing a village churchyard (graveyard) near his mother’s home in rural England. It begins with sublime language describing dusk as it falls over the land then transitions to a meditation on mortality that becomes something of an ode to the common laborers who toiled in England’s fields.

The stanza that captures the heart of the poem: The stanza that always stayed with me is this:

“The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow’r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave,

Awaits alike th’ inevitable hour:

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.”

While pondering the graves of the peasants who endured backbreaking labor most of their lives, it occurred to Gray that their ultimate fate was no worse or better than kings, the rich or the beautiful. [Incidentally, the 1957 Kirk Douglas movie Paths of Glory found its title in this stanza.]

This stanza emblazoned in me then and now the old adage that ‘you can’t take it with you.’ As an old Army colonel I worked with used to say, ‘We’re all headed for the big dirt nap.’ So best to give life our all, whether presidents, CEOs, migrant workers or cashiers at the local grocery store.

You can find the poem here.

0 comments

Write a comment