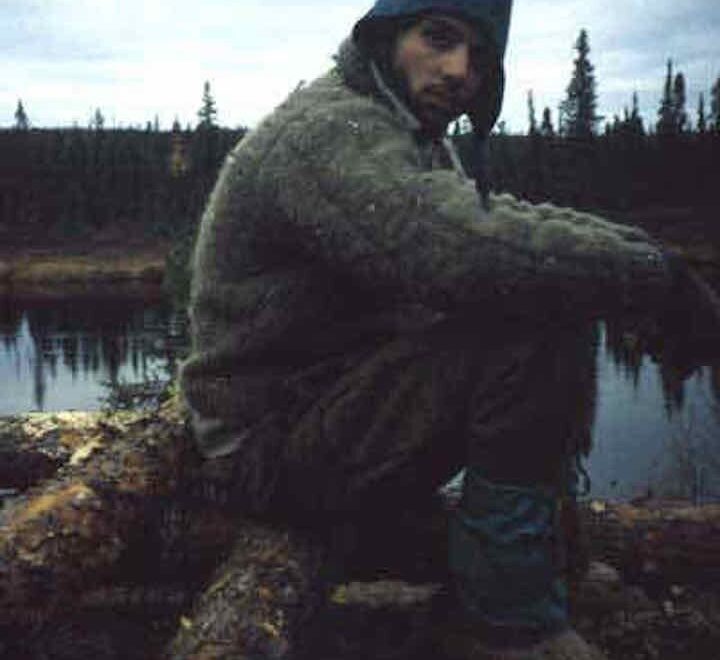

My great friend Scott Power has led a charmed life. He’s intelligent, handsome, huge-hearted, beloved by zillions and has a fantastic wife and two wonderful kids. So when we chatted recently and he singled out 1991 as the single best year of his life, it meant something as he’s had many top-notch years.

What was special about 1991? That was the year that Scott and a friend of his, both twenty, spent a year in Northern Manitoba, 500 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

They lived in a cabin that was constructed, in the middle of nowhere, by Dr. William Forgey in 1975. Scott was working full-time at a publishing company specializing in outdoors type books.

An authors trip sparks an idea

They’d taken a group of authors up to the cabin for a weeklong trip in 1989 and Scott loved it so much he came up with the idea of heading there for a year and writing a book about his experiences.

What the heck does any of this have to do with the human brain? Plenty, as it turns out. For starters, the most important fact influencing humanity right now is this: The human brain is not much different now than it was 200,000 years ago. And the life Scott led that year was the life that our 200,000 year old human brains developed to live in.

What did that life consist of? Upon waking each day, he’d exit the comfort of his warm sleeping bag, shimmy down the loft ladder and put wood into the stove. During the winter the cabin could could forty below zero upon waking so getting that fire going pronto was job number one.

Daily life in the Arctic

Then he melted the ice to make water to make coffee. After breakfast he and his co-adventurer friend Dave would head out and chop up three trees. Yes, three trees. Every day. Why? Because firewood provides warmth and warmth sustains life. They needed to keep an overstock of firewood in case one or both of them got hurt and couldn’t do anything for a week or two or three.

What else do humans need to survive? Food. So most afternoons involved hunting and fishing. Lucky for Scott, the Little Beaver River, which the cabin was next to, was loaded with pike so they had fish aplenty. They also hunted for rabbits, grouse, squirrels and ptarmigan, a partridge-like bird found in the Northern climes.

Scott’s life in the Arctic centered around one thing: Strenuous physical activity in the service of staying alive. It’s that simple. He had to work hard every day for the things we in the “civilized” world take for granted. Like drinking water, which required melting ice. And staying warm, which required wood they’d chopped with axes. And eating food that they caught in a river and hunted in the woods.

Struggle brings gratification

Everything was a struggle, he told me. But it was precisely that struggle that gave him such a profound sense of gratification. To be totally self-reliant empowered him so much more than, as he said,

“Working away at a desk for a frigging paycheck.”

He had no technology to hijack his attention. No phones, no music, no fax machines. No nothing. Just nature.

Scott also spoke of the sounds of the North. What he heard. And what he didn’t hear.

No sounds of honking horns, airplanes flying overhead or jackhammers driving through concrete. There were no sounds of humanity. None.

Only the sound of wind rustling through the trees. The water flowing down the river. And maybe some birds cackling in the sky.

The sound of silence

But the most ethereal of all, Scott said, was the sound of silence. The absence of sound. When do any of us actually experience that?

You know who lived a life similar to this? Our hunter-gatherer ancestors. They also spent their days focused on finding food and shelter. And they didn’t do this in downtown Manhattan. They hunted and foraged in nature. Walking through forests and meadows. Through hills and valleys. Day after day.

And they did this for hundreds of thousands of years. Until roughly ten thousand years ago when they figured out how to grow crops and domesticate animals.

Technology brings humanity insanity

This led, over the succeeding millennia, to villages, towns, cities, empires and now countries. To the invention of guns, ships, trains, airplanes, telegraphs, phones, radio, television, computers, the internet and today’s big kahuna, smartphones.

Well, our brains developed to live the hunter-gatherer life, not the techno-centric world we live in today. What has all this “advancement” wrought? I call it humanity insanity. Put simply, our brains weren’t made to deal with text messages, emails, TikTok and YouTube.

Our brains were meant to deal with what Scott dealt with in 1991. And that is why he was so happy. So energized. So exhilarated by the whole experience. His brain loved it. The whole thing.

The Northern Lights spectacle

There were other otherworldly experiences that also made that year what it was. Scott told me about one winter night when he and Dave went outside in the freezing cold and gazed up at the heavens, in awe as the Northern Lights put on a show like no other. They were spellbound for two straight hours by the majesty of this natural light show in the sky. The enormity of it all brought tears to his eyes.

Then there was the time they were Snowshoeing down the river on Christmas Eve. Darkness prevailed. Then all of a sudden, everything around them illuminated brightly. It was as if a heavenly light switch had been flipped to light their way. They instinctively looked up and witnessed a meteorite burning up above their heads as it entered our atmosphere. Then, as quickly as it started, it was over and they were in the cold dark night again.

The takeaway

So what does all this mean for us? I hope the answer is obvious. Try to get out in nature as much as possible. Even if it’s just a park with some nice trees, gardens and grass. Find a place where the sounds of humanity are minimal, if not completely absent. Go on a camping trip… and leave your phone behind.

All of these will make your brain really happy.

Just ask Scott Power.

Although I steal these moments as often as I can, this is this life my soul longs for! Great article! Thank you 🙏

Thanks, Valerie. Appreciate your reading this. And Happy new year!